The Use of Beneficial Microorganisms in Agriculture

April 2, 2025 | by Aria Thorne

Introduction

Since the dawn of human civilization, agriculture has been an inseparable part of life, driven by the basic need to satisfy hunger. In ancient times, there were no high-yielding crop varieties, no irrigation systems, and no chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Farmers cultivated crops in a natural rhythm, as effortlessly as eating or sleeping, and yet, the fields yielded harvests. For thousands of years, agriculture across the world, including in our country, thrived in this organic harmony without the intervention of advanced technology. However, disruptions to this natural rhythm emerged as humanity’s growing demands led to the adoption of high-yielding and hybrid crops, extensive irrigation, increased cropping intensity, and the widespread use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

In the past, farmers’ homes were surrounded by cattle sheds teeming with livestock, and vast grazing lands stretched freely. The dung and urine from these animals enriched the soil daily, while collected manure from the sheds was stored in pits and later spread across fields. This organic manure nourished the soil, providing food, shelter, and sustenance to billions of microorganisms. Without organic matter, these microbes cannot survive, and without microbes, organic matter cannot decompose. Even the efficacy of chemical fertilizers depends on microbial activity. Thus, unknowingly, traditional farmers fostered an environment where beneficial microorganisms thrived, supporting healthy crops. Pests and diseases existed back then too, but in moderation. Farmers sprinkled cow dung water, garlic extract, cow urine, or homemade liquid fertilizers from decomposed plants to protect their crops—practices documented in ancient texts. This tradition of using organic matter to maintain soil health has flowed through civilizations since time immemorial.

Historical Use of Microorganisms in Pest Control

The use of microorganisms to control pests dates back thousands of years. As early as 2700 BCE, China recognized the presence of pathogenic microbes in bees. Ancient Indian literature also mentions diseases affecting bees. Crops have long been vulnerable to pests like insects, viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, rickettsia, mycoplasma, and nematodes. In 1879, Russian scientist Metchnikoff became the first to demonstrate that infecting the grubs of beetle pests with the fungus Muscadine could control their population, proving the potential of microbial pest management. The fungus Metarhizium anisopliae, for instance, effectively controls the grubs of sugar beet pests like Curculio. Over 3,000 microorganisms are known to infect and eliminate pest insects. In 1926, applying organic manure to San Ford soil increased beneficial microbe populations, successfully controlling potato scab disease. By 1930, researchers observed that antibiotics produced by beneficial microbes could suppress harmful fungi and bacteria.

What Are Microorganisms?

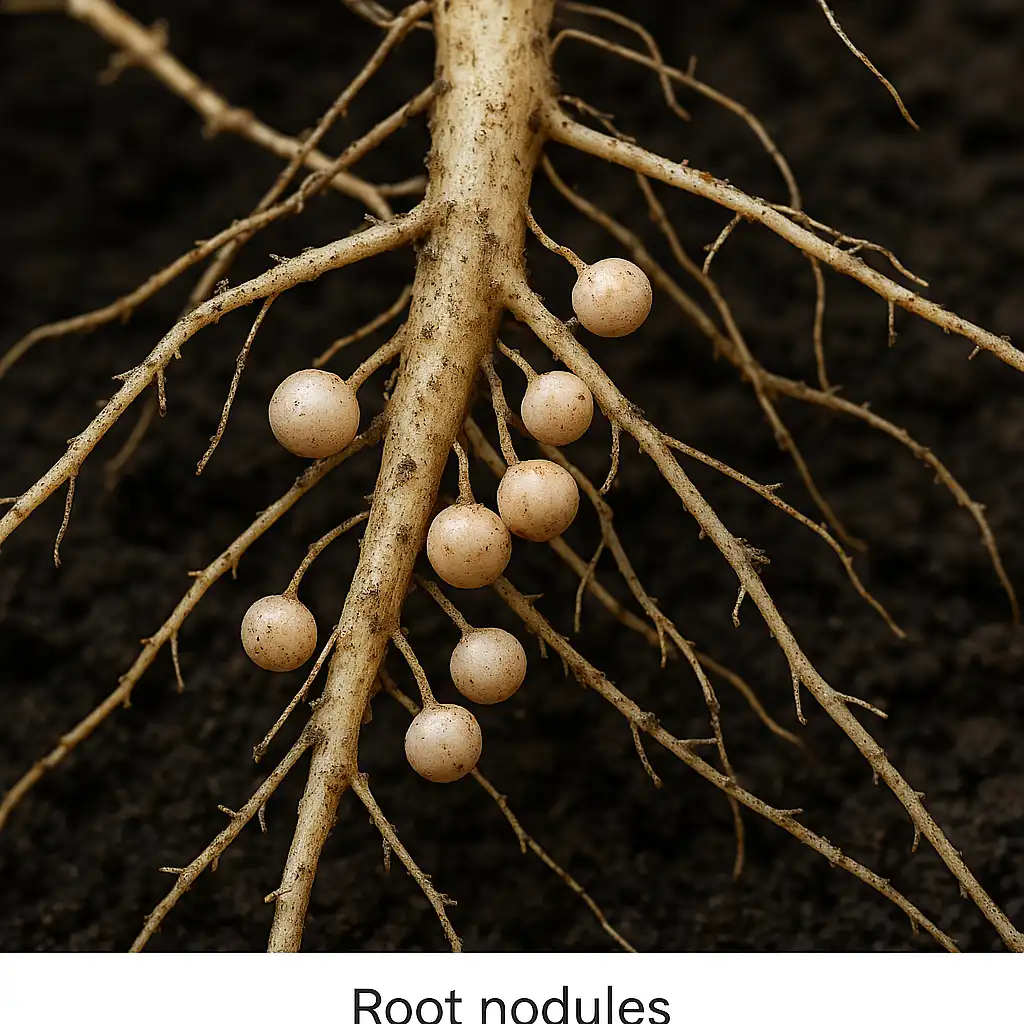

Microorganisms, or microbes, are microscopic living organisms that inhabit nature and influence the nutrition and growth of living beings, both directly and indirectly. While most microbes are beneficial, some can be harmful. As some of Earth’s oldest inhabitants, they exist in water, soil, and air, encompassing bacteria, fungi, viruses, mycoplasma, actinomycetes, and more. These countless microbes play a critical role in creation, sustenance, and decomposition. In agriculture, their impact is profound. Soil-dwelling microbes, fungi, and actinomycetes fix nitrogen from the air, making it available to plants, while others solubilize nutrients like phosphate and potash, ensuring a steady supply to crops. Some microbes, such as Rhizobium, live symbiotically in the roots of leguminous plants, forming nodules that enhance soil fertility. Others operate independently, supporting plant growth. Certain specialized microbes even feed on leaf lipids, aiding plants in return.

In ideal, organic-rich soil, a single gram can host 10 million bacteria, 1 million fungi, and 100,000 actinomycetes. In an acre of soil, up to 15-20 cm deep, there may be 1.8 to 18 billion bacteria. Typically single-celled, bacteria belong to the animal kingdom, while fungi are classified as plants. Remarkably, only 5% of soil microbes are harmful, while the remaining 95% are beneficial. Beyond bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes, certain viruses also help control pest insects.

Commercial Applications of Microorganisms in Agriculture

The traditional rhythm of agriculture in our country faced a significant shift in 1956 with the Second Five-Year Plan, which prioritized agricultural development. At the time, India struggled to feed its population and relied heavily on foreign aid. The slogan “Grow More Food” spurred an urgent push for higher crop production. However, this rapid leap—without a robust foundation—brought mixed outcomes. While food grain production soared, reducing dependency and turning India into an agricultural exporter, it came at a cost. Unregulated use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, over-extraction of groundwater, reliance on high-yielding and hybrid varieties, declining use of organic manure, mechanization replacing traditional plows, and a reduction in livestock numbers have collectively pushed agriculture into a crisis. Today, chemical fertilizers fail to deliver expected yields, and pesticides kill more beneficial insects and animals than pests. Traces of pesticides have been found in cow’s milk and even human breast milk. Over the years, many harmless insects have turned into crop pests. Rising costs of chemical inputs, coupled with reduced subsidies under globalization agreements, have left farmers grappling with an unsustainable system.

Amid this turmoil, a solution has emerged: the use of organic matter and beneficial microorganisms. These ancient allies of civilization—effective, eco-friendly, cost-efficient, sustainable, and simple—offer a way forward. They preserve soil fertility while controlling pests, diseases, and weeds. With chemical inputs becoming prohibitively expensive and environmentally damaging, the commercial use of beneficial microbes has never been more timely. Government, semi-government, and private organizations have stepped up, producing microbial products for agricultural use.

Companies like IFFCO and Hindustan Fertilizer Corporation have introduced biofertilizers to the market, while in high-intensity farming regions like West Bengal, multinational and private firms are tapping into this promising market. However, many of these microbial solutions can be produced by farmers themselves using locally available materials. Empowering farmers to do so could free them from dependency on commercial suppliers.

Also Check – Maize Farming: A Versatile Crop with Immense Potential

Conclusion

The challenges facing modern agriculture—soil degradation, pest resistance, and environmental harm—call for a return to nature’s wisdom. Beneficial microorganisms, nurtured by organic practices, offer a sustainable path to restore soil health, boost yields, and protect crops. Governments have recognized this potential, encouraging fertilizer companies to produce biofertilizers alongside chemical ones. The key now lies in raising awareness and ensuring proper application. By embracing these tiny yet powerful allies, farmers can not only overcome current crises but also build a resilient, eco-friendly future for agriculture.

RELATED POSTS

View all